On March 2020, the new species Oculudentavis khaungraae was described in Nature from a 99 million-years-old tiny skull encased in an amber stone from Myanmar. Its long-toothed mandible, large eyes and short vaulted braincase led the research team to think they were looking at the smallest avian dinosaur ever found, comparable to the smallest living hummingbirds. Researchers concluded that this small flying creature was remotely related to the famous extinct bird Archaeopteryx. Upon this publication, some outside experts were skeptical of the animal’s identity and studies challenging this interpretation quickly followed. The definitive evidence was on the way in the form of a second superbly preserved specimen.

In 2019, Arnau Bolet, ‘Juan de la Cierva’ researcher at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (Barcelona, Spain), along with Juan Daza (Sam Houston State University), Edward Stanley (Florida Museum of Natural History), Susan Evans (University College London) and other colleagues from around the world had started working on a specimen from the same Myanmar mine. Adolf Peretti had contacted Juan Daza to study a large array of fossils in amber, and one of these fossils included a small skull with some postcranial elements, such as a short portion of the vertebral column and the pectoral girdle. The research team was very excited as it showed several morphological features that they had never seen before.

Oculudentavis naga fossil encased in amber as preserved (Photo by Adolf Peretti / Peretti Museum Foundation)

“The specimen puzzled everyone involved at first, because if it was a lizard, it was a highly unusual one”, says Bolet. It was not until a few months after becoming aware of the existence of the holotype of Oculudentavis in a workshop, that they finished their study and concluded that both specimens could be confidently identified as the same lizard genus. Finally, in July, the paper describing O. khaungraae was retracted by its authors, so the brand-new species was wiped out. At least, as a bird.

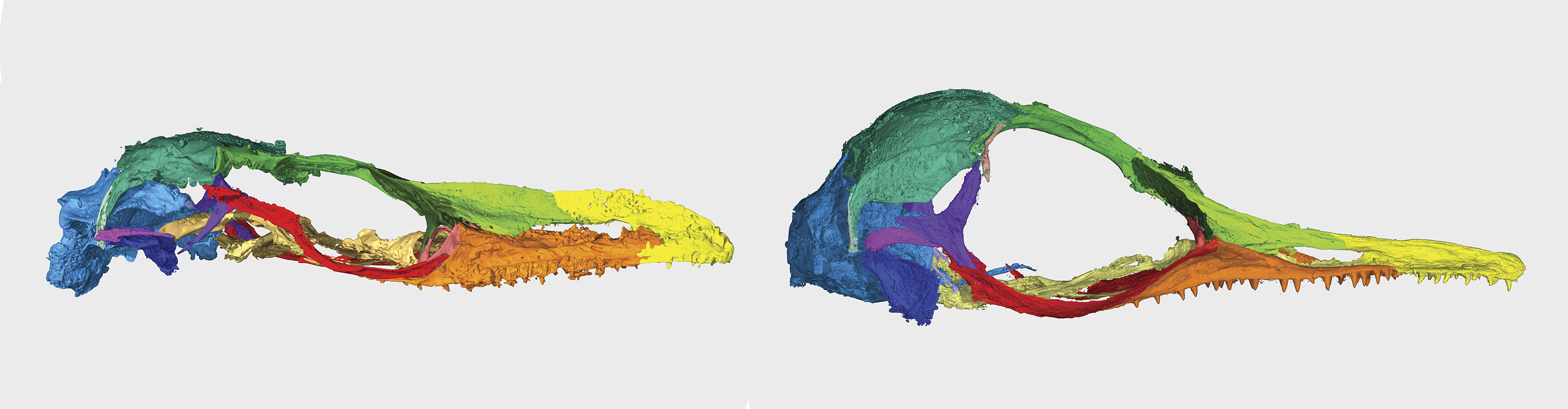

The study upon the second specimen, which is described as a new species within the genus Oculudentavis and named O. naga to honor several ethnic groups native to the northeastern India and northwestern Myanmar. Their study has been now published in Current Biology. Both specimens (the holotypes of O. naga and O. khaungraae) were digitally segmented with a micro computed tomography to provide a detailed description of the individual bones, and to better understand the similarities and differences between them.

“From the moment we uploaded the first CT scan, everyone was brainstorming what it could be,” explains Daza, assistant professor of biological sciences at Sam Houston State University. “In the end, a closer look and our analyses help us clarify its position.” The team also determined both species’ skulls had deformed during preservation. O. khaungraae’s snout was squeezed into a narrower, more beaklike profile while O. naga’s braincase – the part of the skull that encloses the brain – was compressed. The distortions highlighted birdlike features in one skull and lizard-like features in the other. “Imagine taking a lizard and pinching its nose into a triangular shape. It would look a lot more like a bird”, says study co-author Edward Stanley, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Digital Discovery and Dissemination Laboratory.

Comparison of the two specimens of Oculudentavis (O. naga, left and O. khaungraae, right).

“We concluded that both specimens were similar enough to belong to the same genus, Oculudentavis, but a number of differences suggest that they represent separate species”, explains Bolet. In any case, Oculudentavis stands out from other lizards in several features, like the tapering crested snout, the very long mandibles formed by a long dentary and very short post-dentary portion, or the configuration of the palate. These and other morphological features make it an odd-looking lizard, but some key features like the mode of tooth implantation, the shape of the squamosal bone or the way the lower jaw articulates with the skull, fully support this identification.

With all the information, researchers conclude that Oculudentavis was a bizarre lizard, not a bird, and that the bird-like appearance is due to convergence in skull proportions, meaning that “despite presenting a vaulted cranium and a long and tapering snout, it does not really present meaningful morphological characters that can be used to sustain a close relationship to birds”, says Susan Evans, co-author of the research and Professor of Vertebrate Morphology and Paleontology at University College London.

The Oculudentavis naga specimen displays a superb preservation of bone and soft tissue

While Myanmar’s amber deposits are a treasure trove of fossils found nowhere else in the world, the consensus among paleontologists is that acquiring Burmese amber ethically has become increasingly difficult, especially after the military seized control in February. The newly described specimen complies with the ethical guidelines for the use of Myanmar amber set forth by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. It is housed at the Peretti Museum Foundation (Switzerland), whereas the holotype of O. khaungraae is at the Hupoge Amber Museum (China). Peretti’s specimen was purchased from authorized companies that export amber pieces legally from Myanmar, following an ethical code that ensures that no violations of human rights were committed during mining and commercialization and that money derived from sales did not support any armed conflict. The fossil has an authenticated paper trail, including export permits from Myanmar.

Other co-authors of this study are Adolf Peretti (Peretti Museum Foundation, Switzerland), J. Salvador Arias (CONICET - Fundación Miguel Lillo, Argentina), Andrej Čerňanský (Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia), Marta Vidal-García (University of Calgary, Canada), Aaron M. Bauer (Villanova University, United States) and Joseph J. Bevitt (Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, Australia).

Funding for the research was provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation, Sam Houston State University, the Royal Society, the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya, the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences and the Peretti Museum Foundation.

Main image: Reconstruction of life-appearance of O. naga prior to being trapped in tree-resin (artwork by Stephanie Abramowicz / Peretti Museum Foundation)

Original article:

- Bolet, A., Stanley, E. L., Daza, J., Arias, S. J., Čerňanský, A., Vidal-García, M., Bauer, M. B., Bevitt, J. J., Peretti, A., Evans, S. E. Unusual morphology in the mid-Cretaceous lizard Oculudentavis. (2021). Current Biology. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.040