With more than 70 species known to date, Ceratopsians were a diverse clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, one of the more dominant of the terrestrial ecosystems in North America and Asia, having been also reported from the Late Cretaceous of Europe. The group includes the horned-dinosaurs, with iconic genera such as the 7 ton, three-horned Triceratops, which has been featured battling Tyrannosaurus rex in innumerable pop culture outlets. The earliest ceratopsians appeared about 130 million years ago in Asia and the latest species, such as Triceratops, persisted until the end of the Mesozoic era, 66 million years ago.

However, the earlier ceratopsians were small and did not have horns. What they had, like the rest of species of the clade, were large heads, turtle-like beaks, and shearing dentitions, which are thought to have contributed to their evolutionary success. But perhaps most notably, a prominent frill at the back of the skull. In small bodied, early diverging ceratopsians, the frill is relatively short and narrow, but in large bodied (>1,000 kg) ceratopsians, the frill alone can be over a meter in length and width, and constitutes more than half the length of the skull. Although the frill margin is smooth or relatively unadorned in most early diverging species, the horned ceratopsians bear epiparietal and episquamosal ossifications that form a spectacular diversity of structures projecting from the frill, and that distinguish individual species from one another.

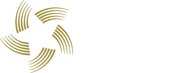

Landmark configuration used to analise the shape of the frill in Centrosaurus apertus (left and middle) and Protoceratops andrewsi (right)

In this study, Albert Prieto-Márquez from the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont and colleagues from the Field Museum of Natural History, the University of Minnessota, Washington University, the American Museum of Natural History and University of California Los Angeles, sought to understand how the frill in ceratopsians evolved through the 65 million years of existence of these animals, as well as during growth of the individuals within a given species. The team performed a battery of statistical and other numerical techniques that allows for examining in a quantitative manner the changes in frill shape in a sample of 25 species. These species represent nearly half the known taxonomic diversity of ceratopsians, from older earlier species like the hornless Protoceratops from Mongolia, to the more recent and enormous Triceratops and the spiked Styracosaurus from the Great Plains of northern North America.

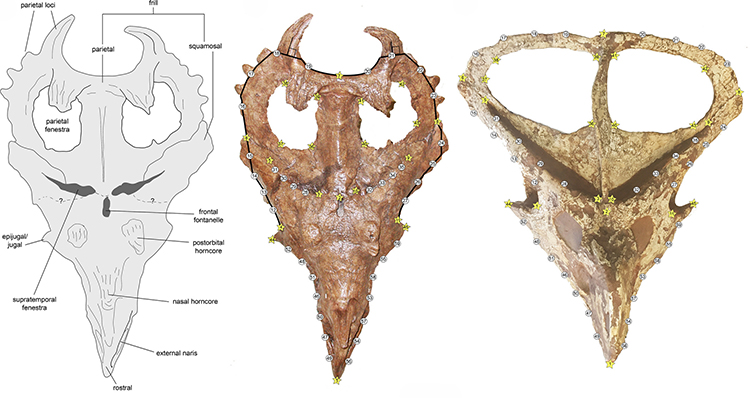

Simplified phylogeny of Ceratopsia with the species included in this study

Paleontologists found that the shape of the frill vary according to clade. Also, that frill morphology became increasingly more disparate through ceratopsian evolution, reaching the highest diaparity in the highly variable frills of later-diverging ceratopsids like Triceratops. Specifically, the frill of ceratopsians became increasingly wider and longer. Most of the variation took place along the corners of the sides and back of the structure. But how did such patterns of variation and those modifications of the frill take place? And what were the implications for the function of the frill?

Results indicate that at some point in ceratopsian evolution, the frill became decoupled from that of the rest of the skull. Ancestrally, in the smaller hornless ceratopsians with poorly developed frills, this structure served primarily for providing attachment sites for muscles involved in feeding. However, as time went on over millions of years, that decoupling of frill shape evolution freed the structure from being constraint to that feeding functionality. The frill then evolved at a faster rate than the rest of the skull. This led to it becoming extremely enlarged and transformed into the bewildering array of ornaments that characterize later species of horned dinosaurs like Triceratops and Styracosaurus.

The acquisition of spikes and pads that characterize the frill of these and dozens of species of horned dinosaurs may have been related to visual display cues within social interactions of these animals, that probably lived in large herds of hundreds of individuals. This study provides the first quantitative evidence supporting previous assertions that peramorphosis played a key role in the evolution of the ceratopsian frill. Peramorphosis is a phylogenetic change in which specimens of a given species mature beyond the traits of its ancestral species, taking on hitherto unseen characteristics.

Main image: Triceratops replica at the museum of the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP)

Original article: Prieto-Márquez, A., García Porta, J., Joshi, S. H., Norell, M. A., & Makovicky, P. J. (2020, published online). Modularity and heterochrony in the evolution of the ceratopsian dinosaur frill. Ecology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6361