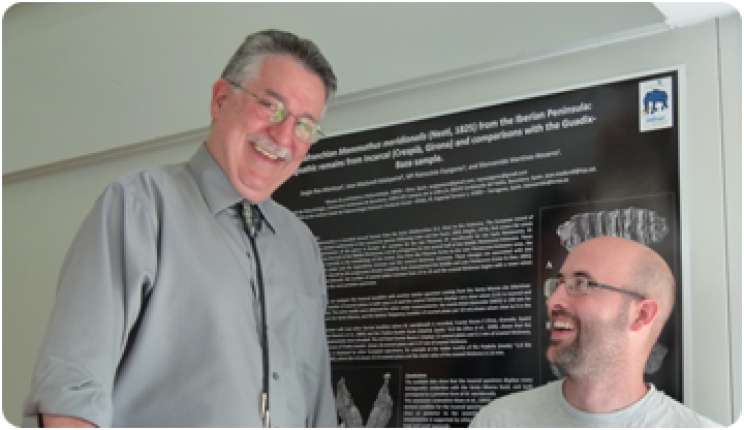

Jacques Gauthier with ICP researcher Arnau Bolet, our expert in cretaceous lizards. Sílvia Bravo. ICP

Jacques Gauthier Professor of Geology and Geophysics and Curator-in-Charge of Vertebrate Paleontology and Curator ofVertebrate Zoology at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History came to ICP to consult our collections. He was interested in our fossil lizards that lived about 125 miion years ago in the Early Creataceous.

Jaques Gauthier (JG): Yes, I am interested in the record of lizards in Spain principally because of the part of time that is represented. Lizards are primarily land-dwellers, and the Early Cretaceous fossil record in North America is mainly from marine sediments. The quality of preservation in ancient Spanish lake beds is superb, and few places on the planet offer such a clear window on a time when the earliest roots of modern biodiversity was emerging.

Gauthier is leading the "Dep-Scaly" group as part of a larger project called “Assembling the Tree of Life”, an initiative supported by the USA National Science Foundation in which scientists are trying to flesh out the basic architecture of the genealogy of all life. They use different technologies to gather all data that can bring information, from high-resolution CT scans of skeletons of fossil and living lizards to DNA sequences, to behaviour, as well as information about when and where lizards (and snakes) lived. Why are lizards so important?

JG: We are interested in understanding how has life evolved, both from a historical perspective -what happened to lizards 65 million years ago following the asteroid impact that exterminated the giant dinosaurs?- and from a mechanistic perspective -how have genes that regulate protein production interacted to turn a normal lizard into a snake? One of the important things is to learn how major morphological transitions were made: from living on land to linving in the ocean, from living on the ground to aerial flight, or from being unable to breathe while running like a lizard to being able to run and breathe at the same time like a mammal. How did evolutionary processes lead to a whale, or a bird, or to humans? Lizards can tell us a lot about these problems.

Reconstruction of a Cretaceous Lizard.

Working in a multidisciplinary team is pushing forward our knowledge of evolution. Looking at lizards they found what seemed to be a contradiction between two data sets. A strong signal in genes supported one lizard tree, but an equally strong counter signal from the anatomy pointed to a different lizard tree. Something was wrong, as you cannot simultaneously be your parents and your children, and there must be only one genealogy of life. But, they found terrific evidences for two different genealogies! This is where they are, trying to figure out what happened, as this pattern has been found in other groups, usually at the deepest branches of the tree, that took place very rapidly and long ago.

JG: The question is what this tells us about our ability to reconstruct the history of life at all. We have tested the method by taking viruses that feed on bacteria. In 72 hours you have thousands of generations, and we can pull some of them out and freeze them: make fossils. We have checked that looking at the DNA we can reconstruct the true tree. This means that the methods we use, they work. So, why don't they work this time?

A better understanding of the tree of lizards is a better understanding of evolution. Darwin basically said that the reason you look like you do is because you inherited that from your mum and dad. But, then, the question is: why not just one species living in every ecological situation all over the planet, rather like Homo sapiens? Why are there so many kinds of living animals?

JG: Today, thousands of species of land egg-laying animals are known. Mammals and reptiles (including birds) form two great branches of the tree of life, but they haven't shared an ancestor since 300,000,000 years ago. In that amount of time we have about 5,000 different mammals, but more than 23,000 reptiles. Given that they have had the same amount of time in which to make new species, why are there so few mamals and so many reptiles? Today, the most diverse reptiles are lizards and birds (10,000 species each). There are only a few species (24) of crocodilians and although they look more like lizards, crocodilians are actually much more closely related to birds (the living dinosaurs). Crocodilians, for example, build nests, protect their young, sing to defend their territory and attract mates. From the anatomy point of view, they both can breathe while they run and have elaborate lungs with air only going into one direction, and many, many other evolutionary novelties. And, although birds (dinosaurs) far outnumber crocodilians today, that was not always the case: 200 million years ago, there were twice as many species of crocodilians as there were species of dinosaurs. What happened?

Birds, they fly. What is the intermediate form between flying and not flying? That was for a long time one of the big problems for scientists and non-scientists to accept evolution. The other was to accept that we humans are all African apes. The answer came through the fossil record of dinosaurs and humans. Jacques Gauthier was one of the first to show with data that birds are dinosaurs.

JG: I, as a graduate student, started to pursue this question, of where birds fit in the tree of life. I assembled some data and I ran some of these programs designed to reconstruct that history... and it was really easy. There were plenty of data supporting that extinct dinosaurs were intermediates between typical reptilian forms and birds. I knew from my education that this was a great debate: were birds dinosaurs or they were they not? But it was so easy to get the answer to such a question for someone who knew lizards!

Again, evolution says: what you look like is not always telling everything about who you are.