Image of the face of Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, popularly known as Pau. Salvador Moyà. ICP

The discovery of a new fossil hominid in a small town in Barcelona in 2002, specifically in a dump, spread worldwide. Boosted by its publication in Science, Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, popularly known as Pau, has played a leading role in the research on the origin of the hominid family for almost a decade. But after more than 20 high-level publications featuring this fossil ape, a new article still reveals characteristics of its anatomy, which confirm Pierolapithecus as one of the earliest hominids ever known.

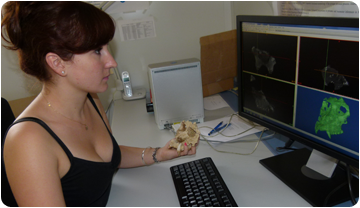

Miriam Pérez de los Ríos, a member of the Research Group of Paleoprimatology and Human Paleontology, is the first author of the article 'The nasal and paranasal architecture of the Middle Miocene ape Pierolapithecus catalaunicus (Primates: Hominidae): Phylogenetic implications’, which goes deep into this hominid face. The research, published recently in the Journal of Human Evolution, applies the technique of computed tomography -the same that can diagnose human diseases and injuries- to discover hidden corners in the fossil remains of Pierolapithecus. As Miriam explains,

This study is a landmark in the understanding of the internal structures of Miocene primates, of which very little is known yet. Moreover, it is a pioneering work in the application of computed tomography in such old primate fossils, as most of the studies have been done with Australopithecus and Homo specimens so far. The knowledge of these structures brings new data to locate Pierolapithecus in the complex network of phylogenetic relationships of primates.

Miriam Pérez de los Ríos working with a CT image of Pau. Sílvia Bravo. ICP

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus is a very unique specimen, the only one we know of this genus and species of hominid that lived about 12 million years ago in the Vallès-Penedès Basin (Catalonia, Spain). More than 80 remains of its skeleton were recovered in the paleontological sites of Abocador Can Mata (els Hostalets of Pierola, Barcelona), among which the splanchnocranium, the already famous face of Pau. Each of these fossils, not to mention its face, are pieces of exceptional value, both for science and heritage.

Direct observation of these fossils has allowed to explore many details, which were gradually disengaging how Pau was: orthograde plan, with an erect torso and shoulder blades at the rear of the back; a relatively long thumb compared to the length of the hand, as also happens in humans and that shows that it could not hang from trees; stereoscopic vision as the top of the nose is in the same plane as both eyes, and many others. But despite how much we have learned about it, there is still a scientific discussion on Pierolapithecus location in the phylogeny of hominids: some scientists clame it was one of the earliest hominids, and some others it was one of the first hominins.

Phylogeny of hominids, following the research published in JHE. Miriam Pérez de los Ríos. ICP

Hominids include all great apes, extant (chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans and gorillas) and extinct; while hominins are a subfamily that includes humans as well as members of their direct evolutionary line, gorillas, bonobos and chimpanzees. Orangutans, extant members of the genus Pongo, are not hominins. The discussion is, thus, whether Pierolapithecus is a hominin or a basal hominid.

The study of the pneumatic structures of the Pierolapithecus skull, the paranasal sinuses, and other structures of the palate and the nasal area, have provided new data into this discussion, pointing once again to Pau as one of the oldest hominids, ie prior to the diversification of early hominins.

With more detail, the observation of the internal structure of the splanchnocranium, thanks to the realization of a high resolution CT, has revealed that his maxillary sinus presents intermediate characteristics between strict pongines (as Sivapithecus and extant orangutans) and kenyapithecines, basal hominoid primates. As happens with orangutans, Pierolapithecus has not a frontal sinus, and lacrimal ducts develop forward as do in pongids and not vertically as in African apes. Other features such as the base of the nasal cavity, which includes the palate, point to a direct resemblance with dryopithecins, as Dryopithecus and Hispanopithecus, extinct European hominids close to pongines. However, these latter structures are not well preserved, and the result cannot be fully assessed. Moreover, the turbinates, bony plates in the nasal cavity to support the soft parts of the nose, are developed very similarly to Pongo.

These data show that Pierolapithecus catalaunicus displayed a mosaic of primitive hominid and derived pongine characteristics, which are inconsistent with the hypothesis that Pau was one of the first hominins. The conclusion of this article, which states that Pierolapithecus, and other driopithecines, are part of a sister group of the extant pongines, will need to be confirmed after the study of craniodental and postcranial data.

+ info About hominoid primates of the Vallès-Penedès basin at the site of the ICP