During the Late Cretaceous, Europe was an archipelago of subtropical islands. The largest of these islands, known as Ibero-Armorica, included the present-day Iberian Peninsula and southern France. Although dinosaurs inhabited both coastal and inland environments in this region, most previous paleoecological studies have focused on continental areas such as North America. As a result, until relatively recently, European island ecosystems and their differences from continental ecosystems remained largely unexplored scientifically.

Now, a research team led by the Dinosaur Ecosystems Research Group at ICP-CERCA and the Museu de la Conca Dellà has reviewed, completed, and updated a record of more than 700 fossil discoveries of dinosaurs in the Iberian Peninsula and southern France, covering the period between the Upper Campanian and the Upper Maastrichtian, from 76 to 66 million years ago, the final stage before the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs worldwide. This database is the most comprehensive at the national level and one of the most detailed in Europe. Each entry includes information on classification, location, age, geological formation of origin, and, most importantly, the interpretation of the environment in which the fossil remains were deposited.

"With this record, we have taken a first step in better understanding how Ibero-Armorican dinosaurs interacted with their environment," explains Bernat Vázquez, researcher at ICP-CERCA and MCD and first author of the paper. "This allows us to explore questions such as the distribution of these dinosaurs across the territory, the reasons for this uneven distribution, and whether there were more favorable environments for certain groups within the island."

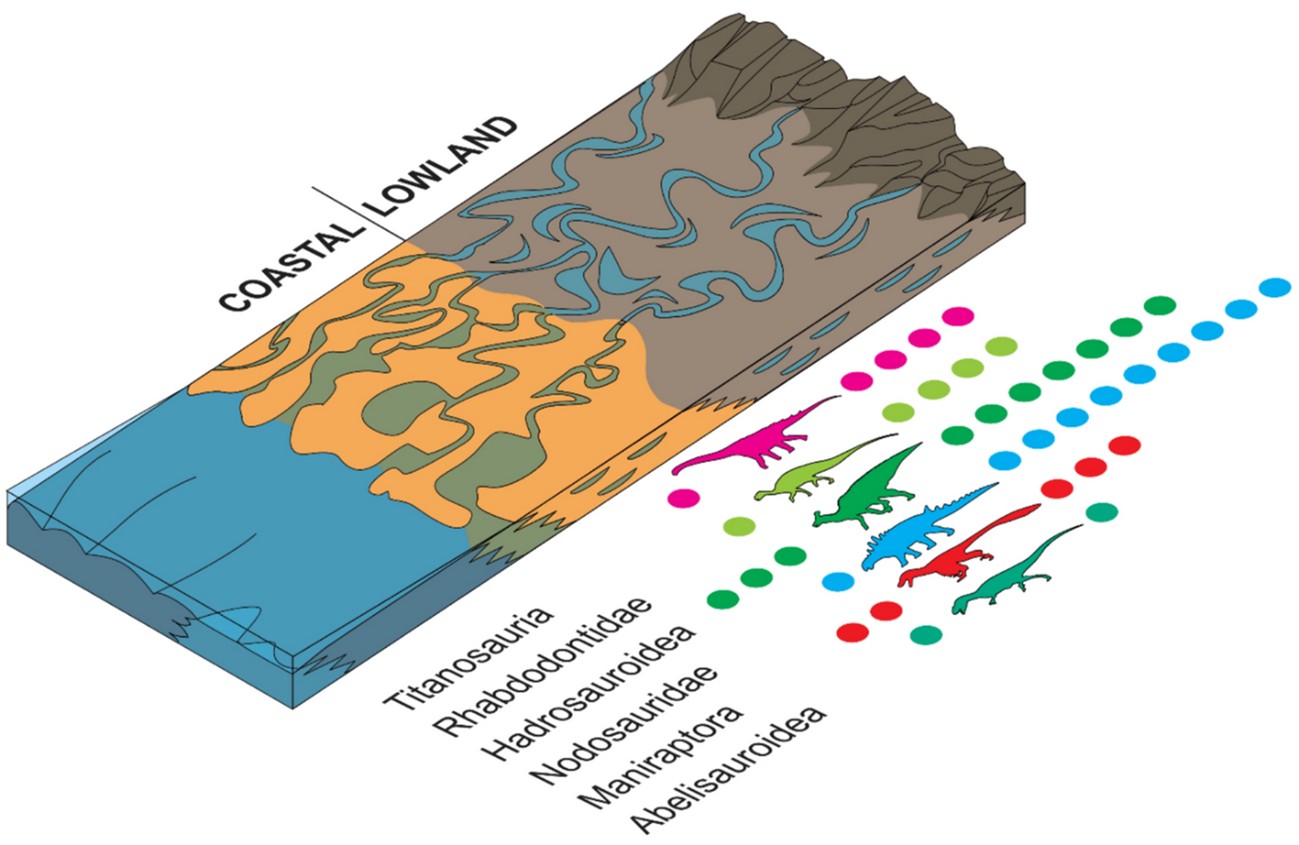

The study's results indicate that herbivorous dinosaurs, such as nodosaurid ankylosaurs, titanosaurian sauropods, and ornithopods (hadrosauroids and rhabdodontids), preferred to live in continental environments such as mid-river courses, lakes, and inland forests rather than coastal environments like lagoons, deltas, marshes, and beaches. Additionally, the study of titanosaurian sauropod fossil remains has confirmed that these animals had a preference for nesting in fluvial or inland environments. In the case of carnivorous dinosaurs, smaller-sized maniraptorans also showed a preference for inland environments. In contrast, large predators such as abelisaurids had a more uniform distribution, without a clear preference for any particular environment.

Image 1. Habitat preferences of different dinosaur groups in the Ibero-Armorican region (southwestern Europe) during the Late Cretaceous. (Reproduced from Vázquez López et al., 2025). The colored circles indicate the proportion of individuals present in each environment to visualize each group's preference.

The research provides new insights into the effects of the so-called "Maastrichtian faunal exchange," the moment when many new species arrived on the island, such as hadrosauroids," explains Albert Sellés, researcher at ICP-CERCA and MCD. He adds that "this arrival generated competition with species that were already present, which led to significant changes in the island's ecosystems." This competition could explain why some native dinosaur groups, such as rhabdodontid ornithopods, became extinct between 72 and 69 million years ago. "We believe that the presence of better-adapted hadrosauroids progressively reduced the habitat of rhabdodontids, which could not compete for the same resources," adds Sellés.

On the other hand, titanosaurs and nodosaurs appear to have been unaffected by this event. "Unlike ornithopods, these groups probably occupied a different ecological niche that did not directly compete for the same resources," notes Albert Prieto, researcher at ICP-CERCA and MCD. This could explain why they maintained their presence without significant changes while other dinosaurs, such as rhabdodontids, disappeared. "These findings help us better understand how different dinosaur groups coexisted and adapted within these island ecosystems," concludes Prieto

The Pyrenean dinosaurs, the last in Europe

This research further highlights the exceptional fossil record of dinosaurs in Catalonia. The Pyrenean fossil sites contain the remains of the last dinosaurs that lived in Europe, just millions or even thousands of years before their global extinction. The fossils they provide are a key resource for paleontologists and also an invaluable source of content for interpretation centers and museums in the region, which disseminate this unique paleontological heritage. The interest in Pyrenean dinosaurs lies in the fact that they represent the last documented groups in Europe, providing crucial information about ecosystems before the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

Main image: Reconstruction of a Late Cretaceous floodplain with titanosaurian dinosaurs (right, central position), lambeosaurines (background), the ornithopod Pararhabdodon isonensis (left), and a dromaeosaurid (bottom right). (Oscar Sanisidro / (C) Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont).

Research article:

- Vázquez López, B. J., Sellés, A., Prieto-Márquez, A. & Vila, B. (2025). Habitat preference of the dinosaurs from the Ibero-Armorican domain (Upper Cretaceous, south-western Europe).. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, 144, 4 . https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-024-00346-1