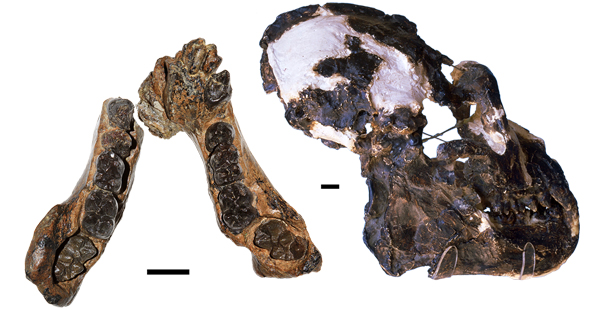

In 1872, the extinct ape Oreopithecus bambolii was described based on a mandible from the Late Miocene of Tuscany (Italy). Many years later, in 1958, a remarkably complete (even if crushed) articulated skeleton of Oreopithecus was discovered. As a result, Oreopithecus is one of the best-known Miocene apes. Yet, its phylogenetic (kinship) relationships have been highly controversial. The oreopith part of an endemic insular fauna that, about 8 to 7 million years ago (Late Miocene), was distributed in an archipelago that comprised current Tuscany and the island of Sardinia. In 2022, I gave a talk at a meeting that commemorated the 150th anniversary of the original description of Oreopithecus, and the long version of this talk was published in 2024 in a special volume of the Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. This review article aims to contextualize the oreopith within the framework of Miocene ape evolution and critically evaluate the multiple phylogenetic hypotheses proposed during the last decades.

In the past, the oreopith was considered an Old World monkey (cercopithecoid), an ape (hominoid), a primitive simian (i.e., an ancient lineage of the group that includes monkeys, apes, and humans), or even distant human ancestor. In the 1980s, the hominoid status of Oreopithecus gained general acceptance, but its closest evolutionary links remained hotly debated. The problem is that the oreopith combines a peculiar tooth morphology with a rather primitive skull and a seemingly specialized locomotor skeleton (which, in several aspects, resembles that of modern apes). Based on dental similarities, some authors supported a close link with a group of primitive apes (the nyanzapiths) from the Early to the Late Miocene of Africa. Others considered it was broadly ancestral to the group including extant apes, namely hylobatids (lesser apes) and hominids (great apes and humans). Finally, others considered Oreopithecus a direct descendant of European Miocene great apes (the dryopiths), mostly based on similar locomotor adaptations and a few cranial similarities. The nyanzapith and dryopith hypotheses have different paleobiogeographic implications (African vs. European origin), illustrating the major problems faced when trying to reconstruct the evolutionary history of Miocene apes generally. What does the current evidence tell us?

The few cranial similarities of the oreopith with modern great apes might be related to its large body size (more than 30 kg in the males, slightly smaller than a female orangutan) and its overall cranial morphology appears more primitive, resembling hylobatids and more basal apes from Africa (such as nyanzapiths). Its peculiar dental morphology also shows detailed resemblances to that of nyanzapiths. This is why some recent phylogenetic analyses support a link with nyanzapiths. This would indicate that the modern ape-like locomotor adaptations of Oreopithecus evolved independently, as a result of similar selection pressures. This is not surprising at all because, in all probability, it also applies to various extant hominoid lineages. Indeed, it was recently suggested that postcranial convergence is causing a lot of confusion in Miocene ape phylogenetic reconstruction.

All in all, current evidence supports the oreopith as a late descendant of nyanzapiths, which would have dispersed from Africa into the Tusco-Sardinian Archipelago during the Late Miocene and acquired particular dental and locomotor adaptations under insularity conditions. However, further research is required to confirm further this hypothesis. Be that as it may, we should stop considering Oreopithecus as just an oddball insular primate, as it might just be the tip of the iceberg of problems related to Miocene ape phylogeny. Rather than shoehorning the oreopith into the current paradigm of ape evolution, we should be ready to explore alternative (even if unorthodox) hypotheses. Oreopithecus is more than a mystery to be solved—it is key for disentangling the puzzle of Miocene ape phylogeny.

Main image: The type mandible of Oreopithecus bambolii (left) and skull of the 1958 skeleton (right). Photographs by S. Bartolini-Lucenti and E. Cioppi, reproduced from Alba et al. (2024: figs. 4a1 and 7a2), respectively.

SOURCE OF THE NEWS: UAB Divulga / Author: David M. Alba (ICP-CERCA)