Despite having lizard like claws, scales and tails, the ancient animals, known as albanerpetontids – mercifully called “albies” for short –, were amphibians, not reptiles. Their lineage was distinct from today’s frogs, salamanders and caecilians and dates back at least 165 million years, dying out only about 2 million years ago.

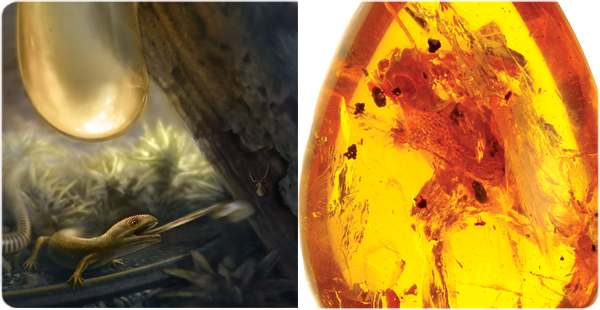

Now, a set of 99-million-year-old fossils redefines these tiny animals as sit-and-wait predators that snatched prey with a projectile firing of their tongue –and not underground burrowers, as once thought. The fossils, one previously misidentified as an early chameleon, are the first albies discovered in modern-day Myanmar and the only known examples in amber.

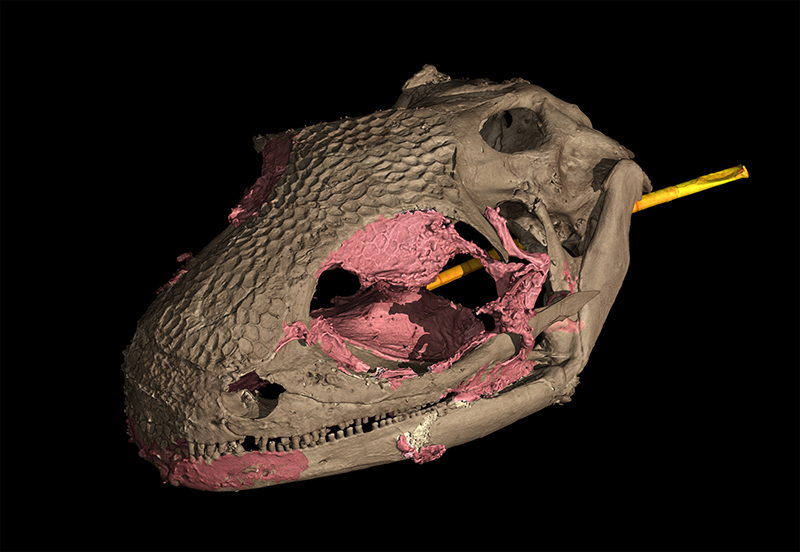

Researchers performed CT scans of the amber pieces in order to obtain high-resolution images of their anatomy that revealed even some soft tissue, including the tongue pad and parts of the jaw muscles and eyelids.

CT scanned skull of and adult specimen of Yaksha perettii. Author: Edward Stanley/Florida Museum of Natural History/VGStudioMax3.4

Fossil remains represent the new genus and species Yaksha perettii, named after treasure-guarding spirits known as yakshas in Hindu literature and Adolf Peretti, the discoverer of two of the fossils. Based on an adult fossil skull, Juan Diego Daza, lead author of the Science study and assistant professor of biological sciences at Sam Houston State University (Texas, USA) estimates the Y. perettii was a small animal, about 5 centimeters long, not including the tail.

“We envision this as a stocky little thing scampering in the leaf litter, well hidden, but occasionally coming out for a fly, throwing out its tongue and grabbing it”, says Susan Evans, professor of vertebrate morphology and paleontology at University College London that coauthored the research.

The chameleon tongue is one of the fastest muscles in the animal kingdom and can rocket from 0 to 100 km/h in a hundredth of a second in some species. It gets its speed from a specialized accelerator muscle that stores energy by contracting and then launching the elastic tongue with a recoil effect. If the earliest albies also had ballistic tongues, the feature is much older than the first chameleons, which may have appeared 120 million years ago. Fossil evidence indicates albies are at least 165 million years old, though Evans says their lineage must be much more ancient, originating more than 250 million years ago.

“We studied the kinship relationships between known albies species and with other extant and extinct amphibians”, explains Arnau Bolet, ‘Juan de la Cierva’ researcher at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP), who collaborated in the analysis performed to the new species. “We have seen that some specimens that were thought to belong to Albanerpeton, a genus that lived for more than 125 million years, belong, at least, to two different genera. This interpretation is consistent with the phylogenetic position we propose for Yaksha perettii”, says.

“The amazing level of preservation of the fossil specimens has provided very useful information to infer the behavior of these small amphibians. Unfortunately, this group is so specialized that, even if we include the new morphological information, we still can’t tell their exact position in the amphibian phylogenetic tree”, explains Bolet.

Albies died out due to unknown causes only 2 million years ago.

Other study co-authors are J. Salvador Arias of Argentina’s Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET); Andrej Čerňanský of Comenius University in Bratislava (Slovakia); Joseph Bevitt of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization; and Philipp Wagner of Allwetterzoo Münster (Germany); and Aaron M. Bauer, from the Villanova University (USA).

3D digitized specimens are available online via MorphoSource. The adult skull is housed at the Peretti Museum Foundation in Switzerland, and the juvenile specimen is at the American Museum of Natural History.

Main image. Left: Reconstruction of a Yaksha perettii specimen hunting before being trapped in a tree resin drop. Author: Stephanie Abramowicz - © Peretti Museum Foundation / Right: Yaksha perettii fossil specimen trapped in amber. Author: Adolf Peretti - © Peretti Museum Foundation

Original article: Daza, J.D., Stanley, E.L., Bolet, A., Bauer, A.M., Arias, J.S., Čerňanský, A., Bevitt, J.J., Wagner, P., Evans, S.E. (2020). Enigmatic amphibians in mid-Cretaceous amber were chameleon-like and had ballistic feeding. Science, 370 (6517): 687-691. 10.1126/science.abb6005

3D interactive model: