Reconstruction of Jordi, in exhibition at the ICP Museum in Sabadell. Laura Celià. ICP

This week, a team of researchers at the ICP has published in the prestigious 'Journal of Human Evolution’ an accurate reconstruction of the paleoenvironment where the fossil hominid Hispanopithecus laietanus, popularly known as Jordi, lived in. This research delves into the causes that led to the extinction of the hominids who inhabited Europe during the Miocene, between 15 and 9 million years ago. The fossil remains of this primate found in Catalonia are the latest known in Western Europe, and therefore are important for understanding the extinction of the European great apes in the Late Miocene.

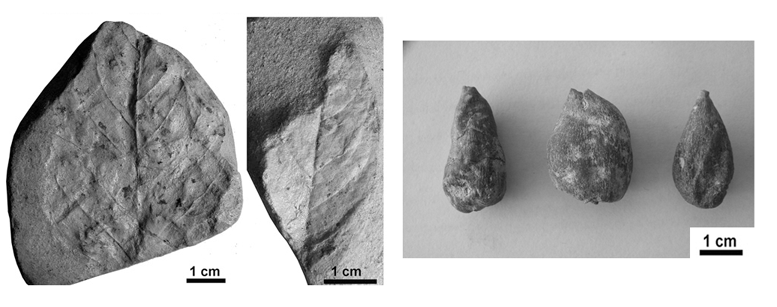

The fossil plant remains recovered in the excavations made during summer 2010 by a team of ICP at Can Llobateres (Sabadell) have a good degree of preservation and are more diverse than those known so far. This site, discovered in 1926, is internationally known for the disovery of the most complete fossil hominid Hispanopithecus laietanus, corresponding to the partial skeleton of an adult male that Salvador Moyà and his team named as Jordi. The botanical remains belong to fossiliferous layers near those where hominid remains were found, which has allowed to recover plenty of data on the paleoenvironment where this primate lived. The results are included in the article 'The paleoenvironment of Hispanopithecus laietanus as Revealed by paleobotanical evidence from the Late Miocene of Can Llobateres 1 (California, USA)’, now published online, signed by the paleobotany expert Josep Marmi and other ICP researchers.

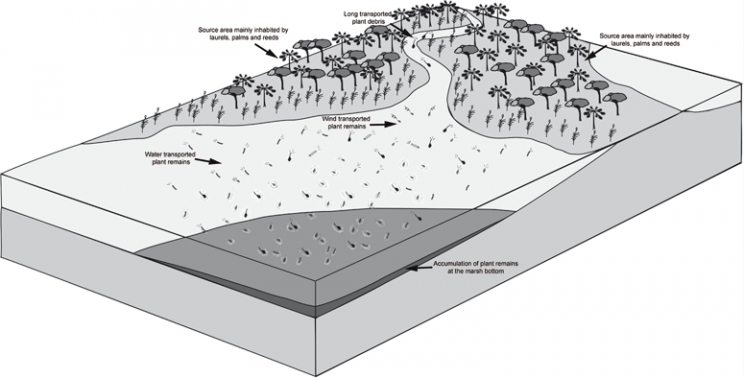

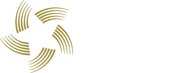

Diorama of Can Llobateres region during the Miocen, when Hispanopithecus lived there

Among the recovered plant remains, ferns, palms, bamboo and other aquatic herbaceous plants, as well as a type of laurel and oak remains are included. This fossil set has enabled researchers to reconstruct the paleoenvironment in which Hispanopithecus lived, much more accurate than previous studies had achieved. Research shows a habitat between tropical and subtropical, which due to climatic changes that occurred later in the Miocene, would gradually reduce its tropical elements and, therefore, undergo significant changes in vegetation. These changes are precisely those that could explain the extinction of Hispanopithecus more than 9 million years ago.

The Eurasian hominids, originating from African ancestors dispersed to Europe and Asia around 15 million years ago, underwent a major adaptive radiation in these continents. However, after a few million years and due to climatic changes and the consequent changes in vegetation, their decline began. Initially, hominids in western and central Europe (as Hispanopithecus) became extinct, just over 9 million years ago - with the exception of Oreopithecus, living in an archipelago that define the current Tuscany and Sardinia, who died out about 7 million years ago. Later, forms of Eastern Europe and gradually in Asia -where orangutans from the islands of Sumatra and Borneo are currently the last representatives of the Eurasian radiation of hominids- also became extinct.

Therefore, the fossil record of hominoids in Catalonia, both for the number of represented species and their temporal scope, is very important to understand not only the radiation of hominids in Europe, but also the factors that determine their subsequent extinction. And Hispanopithecus is, as far as we know, the last of this saga.

Hispanopithecus, a subtropical climate primate

The richness of the megaflora recovered in 2010 excavations, as well as fossil remains of figs found in the middle of last century, allow us to make an accurate paleoenvironmental reconstruction of the region where Jordi lived in. According to ICP researchers we find a landscape that would present a mosaic of wetter forest areas near water bodies typical of subtropical climates (where Hispanopithecus would live) and more open and wooded areas with a higher proportion of deciduous trees due to greater seasonality.

Some fossil remains recently found in Can Llobateres (left) and the fossi figs fòssils recovered last century.

The recovered plants indicate a marshy area with reeds, palms, ferns, and evergreen laurel and ficus trees, which is consistent with the faunal record of this sire, typical of wet forest environments. Hispanopithecus would have preferred the lowlands wet areas, where he could find fruit throughout the year.

In fact, this environment would have been more common in the Vallès-Penedès Basin between 12 and 9.6 million years ago, but subsequent climatic changes caused the disappearance of tropical elements, leading to a dominance of deciduous trees also in the wetlands. This would have left Hispanopithecus without enough food during the unfavorable season, ultimately leading to extinction.

These same factors were involved in the extinction of other hominids in Europe, although given the complexity of local paleoenvironmental changes associated with climate change other factors would be to consider, especially in Eastern Europe and Asia.

Can Llobateres, a site of reference in the Catalan Miocene

The paleontological site of Can Llobateres, in Sabadell, is one of the richest of all European Neogene with over 70 species of mammals recorded. However, it was the discovery of the remains of the most complete hominoid primate Hispanopithecus laietanus, popularly known as Jordi, what made this site internationally known.

Among the recovered fossils there are terrestrial and freshwater mollusks, as well as a large number of terrestrial vertebrates, and above all, micro- and macromammals. Among the latter are the equid Hippotherium, four species of rhinocerotids, four different swines and ruminants, as well as a variety of carnivores (felids, hyaenids, ursids, and mustelids, among others), to which the fossil hominoid Hispanopithecus must be added.

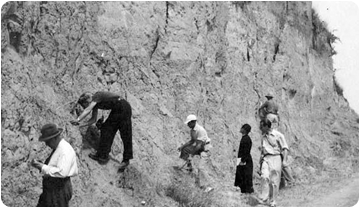

Crusafont and collaborators during field works in Can Llobateres. Arxiu de l'ICP

The site was discovered in 1926 by Miquel Crusafont and Ramon Arquer during the construction of the road from Sabadell to Mollet. The initial survey along with the remains recovered during the operation of a clay quarry led to systematic excavations since 1958. That year the first fossil hominoid remains were recovered. Therefore, the classic collections already included dental remains of Hispanopithecus, but it was not until the 1990s when a team led by Salvador Moyà, current director of ICP and then a researcher at the Institute of Paleontology in Sabadell, recovered a partial skull and skeleton of this species. These remains are known as Jordi.

After more than a decade without excavations, ICP resumed field works in 2010 under the direction of the researcher David M. Alba. The aim was to recover new remains of Hispanopithecus, but also other remains that could allow a taphonomic and paleoenvironmental study. The work just published represents the first results based on these recent excavations. However, results based on 2011 field work will soon provide new surprises.