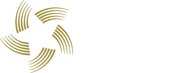

Face of Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, found in 2002 in Abocador de de Can Mata (Els Hostalets de Pierola, Anoia). Photo: ICP.

Food specialization that allowed the expansion of great apes from Africa to Eurasia 14 million years could also have been responsible of their extinction. A study published today in PLOS ONE by a team of researchers from the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont infers the diet of five hominoid species from the Iberian Peninsula through the analysis of enamel scratches and compares the results with those from other species of Europe. A climate change would have reduced the availability of their main food and species would not have adapted to other food resources.

After an initial radiation in Africa 23 million years ago, hominoids began to disperse through Eurasia 14 million years ago where they diversified into multiple great ape species. The greatest example of this diversity can be found in the Vallès-Penedès sites (Catalonia, Spain), that have provided new species of this group since the mid-twentieth century, such as Pierolapithecus catalaunicus (the hominoid found in Els Hostalets of Pierola and described by the specimen popularly known as “Pau”), Anoiapithecus brevirostris (the only member is nicknamed “Lluc”) or Hispanopithecus laietanus (known as “Jordi” and extinct 9 million years ago).

A. Reconstruction of the face of Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, by Meike Köhler. B. Reconstruction of Anoiapithecus revirostris, by Marta Palmero. C. Reconstruction of Hispanopithecus laietanus, by Ramon López. Photo:ICP

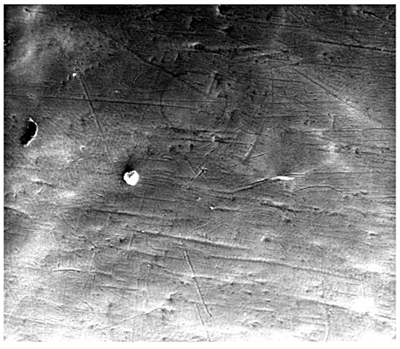

Although several articles haven been published on paleobiological and ecological aspects of this species (the type of locomotion they had, how the ecosystem where they lived was, etc.), not before their diet had been studied from the pits and striations that the food they ate left on their teeth. Each type of food produces characteristic microscopic marks on the enamel that paleontologists can identify and associate to a type of diet by comparing them with current species, whose diet is known. As it’s usually said, "we are what we eat."

The analysis of these marks revealed that great apes species of the Miocene had a diverse diet and it was not based on leaves and shoots, as it was previously thought. While Pierolapithecus catalaunicus ate hard foods (such as tree nuts or seeds), Hispanopithecus preferred softer fruits. Likewise, other species alternated a combination of both types of food depending on the environment they lived, an uncommon feature in current species of primates.

Examples of food enamel marks in Anoiapithecus brevirostris in an electronic microscope. Photo: Daniel DeMiguel (ICP)

This research, published today in the journal PLOS ONE by a team of researchers from the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont headed by Daniel DeMiguel, specialist in dental wear and diet reconstruction, has also analyzed the diet of other species of European great apes which also exhibit this pattern of specialization, but with some differences. While Catalan species fed mainly on trees (as extant orangutan does), species from eastern Europe spent more time on the floor. In some cases, the extinct taxa lack clear extant dietary analogues.

The study relates this diversity in diet with the beginning of a climate change towards cooling and increased seasonality. "The high behavioral plasticity of extant great apes probably allowed them to survive in front of a marked environmental instability. They adopted different diets as a response to the increased environmental heterogeneity. This fact would have minimized the competition for resources”, says Daniel DeMiguel. In some cases, food specialization can also be linked to the development of new locomotor adaptations. Thus, the suspensory adaptations of Hispanopithecus species enabled a more efficient foraging on terminal branches.

Surprisingly, this dietary specialization that allowed them to adapt to different environments and survive, could also have been the cause of their extinction. When more drastic paleoenvironmental changes took place, the habitats of these species were fragmented and their favorite food became scarce during long periods. In central and western Europe, these species did not adapt to other types of food and became extinct between 12 and 9 million years, while species from Eastern Europe disappeared 7 million years ago.

The study used 15 molars of 5 different species of apes in the Iberian Peninsula: Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, Anoiapithecus brevirostris, Dryopitecus fontani, Hispanopithecus crusafonti and H. laietanus, and 4 species from Western Eurasia, found in Greece, Italy, Hungary and Turkey. Griphopithecus alpani, Hispanopithecus hungaricus, Ouranopithecus macedoniensis and Oreopithecus bambolii To infer their diet, samples were compared with tooth of current primate species such as chimpanzees, gorillas and baboons, whose diet is known.

+ info: DeMiguel, D., Alba, D.M. & Moyà‐Solà, S. (2014). Dietary specialization during the evolution of western eurasian hominoids and the extinction of european great apes. PLOS ONE. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097442