66 million years ago, the asteroid that hit our planet led to the demise of the iconic dinosaurs and many mammalian groups. However, some mammalian lineages survived and partly gave rise to modern placental mammals that we know today including us, cats, bats and whales called crown clades. Other placental mammals known as archaic groups, only survived until about 30 million years ago and went extinct. This time no asteroid could be blamed and it is still unclear why these groups disappeared.

“To bring light to this mystery, we decided to explore the senses and behaviours of these archaic group of mammals”, explains Ornella Bertrand, main author of the recent article published in Journal of Anatomy and researcher at the ICP. Since it is impossible to study the behaviour of extinct species the same way as modern-day mammals, paleoneurologists use the imprint of the brain against the endocranial cavity to study its morphology and the difference in proportions existing between brain regions. “This gives us an idea of the behaviour of the animal. For instance, large olfactory bulbs translate into an enhanced sense of smell”, clarifies Bertrand.

The advancement of CT (Computer Tomography) scanning technologies over the last few decades has allowed paleontologists to use this technique to see what is inside a fossil. This is very similar to getting an MRI done in a hospital.

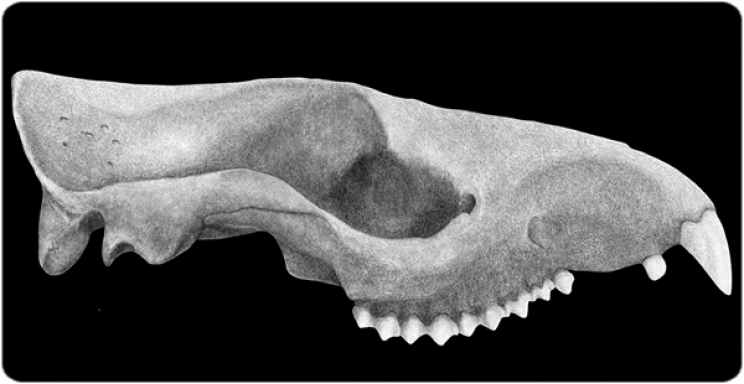

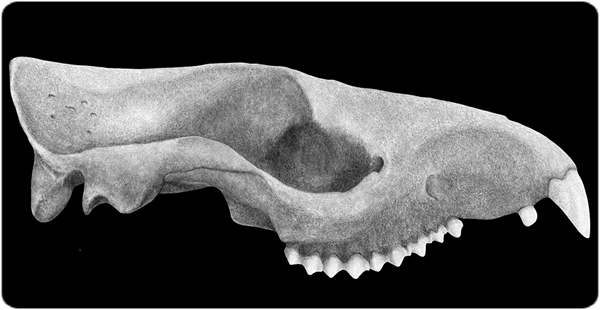

The fossil skull that they CT scanned belong to Tillodontia, an enigmatic group of mammals that lived from the Paleocene to the Eocene, during the Cenozoic era. These mammals originated in Asia and migrated to North America and Europe. They belong to a group called Laurasiatheria and are distantly related to modern mammals. “Trogosus had a peculiar appearance, nothing that we would see today. This animal was close to the size of a medium size wild boar”, claims Marina Jimenez Lao, who worked on this project for her Master thesis at the School of GeoSciences from the University of Edimburgh. It may have put more weight on its hindlimbs, and used its forelimbs to unearth roots and tubers thanks to large and recurved claws. “Even more strange, it also had rodent-like and ever-growing incisors like squirrels and rats”, explains this coauthor of the research article.

All specimens described in this paper are from North America and the best-preserved specimen of Trogosus hillsii is from the upper Huerfano Basin in Colorado (USA), which corresponds to the middle Eocene with an estimated age between 52-48 Million years old. The cranium is relatively well-preserved including a complete braincase, but lacks parts of the rostrum.

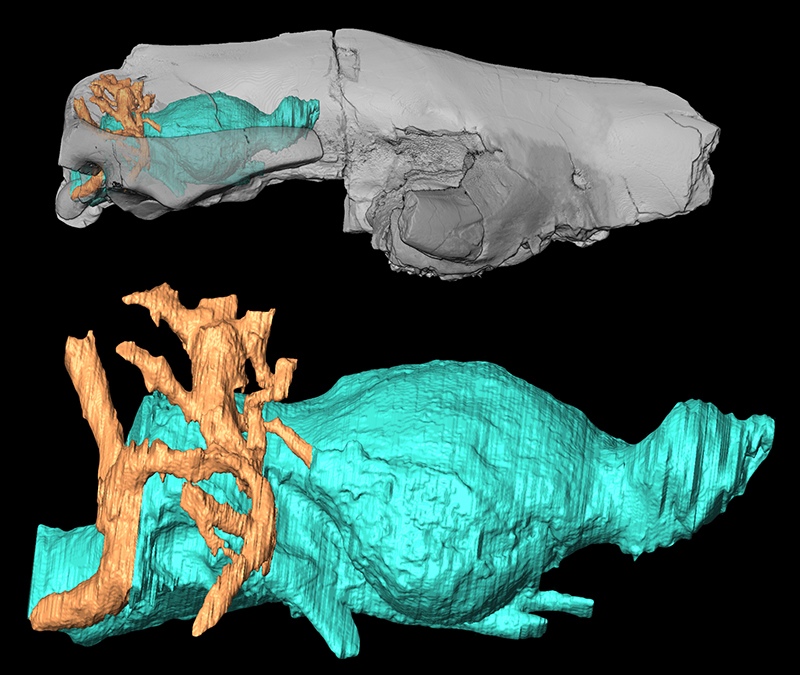

One interesting aspect from using CT data was discovering that in the back of the cranium, a large number of vessels that drained the brain of Trogosus was present. In the 1950s, Charles Gazin, an American paleontologist created a physical endocast using another specimen. He noticed that the endocast included an unusually large cerebellum that did not show any clear structures. Thanks to CT scanning, Bertrand and her team showed that there is a complex set of canals that surrounds the cerebellum and most likely collapsed after the animal died, which would have made the endocranial cavity much larger than it actually was.

Brain and vessels virtual endocasts inside the translucent cranium (top), brain and vessels virtual endocasts (bottom) of the middle Eocene Trogosus hillsii (USNM 17157) from the Huerfano Basin, Colorado.

Credit: Line drawing done by Sarah Shelley (modified version appearing in Bertrand et al. 2022).

One particular aspect that Bertrand and her colleagues studied was the proportion of different brain regions. The neocortex is a portion of the brain present in all mammals and that specifically integrates sensory and motor information together. Species with large neocortices, display more elaborated behaviours such as complex social behaviour or enhanced vision. “We have seen that the neocortex was relatively smaller in Trogosus and in other archaic herbivores compared to contemporaneous archaic carnivoran species and herbivorous crown clades”, states Bertrand. The researchers hypothesized that Trogosus and other archaic placental herbivorous mammals may have been outcompeted by crown herbivores (such as the ancestors of ruminants or boars) for the same resources, and may have been less well-equipped to escape predators than crown clades that had more complex behaviours.

Climatic fluctuations may have also played a role in the disappearance of the group. Tillodontia were relatively specialized by the end of the Eocene, which could have led to their extinction because of a lack of behavioural flexibility. Within this group, Trogosus survived for millions of years before going extinct and this animal was probably relying more on it sense of smell than other senses such as vision.

Original research article:

- Bertrand, O. C., Jiménez Lao, M., Shelley, S. L., Wible, J. R., Williamson, T. E., Meng, J. & Brusatte, S. L. (2023, published online) The virtual brain endocast of Trogosus (Mammalia, Tillodontia) and its relevance in understanding the extinction of archaic placental mammals. Journal of Anatomy. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13951