A critical step in the history of humankind is the emergence of bipedal locomotion in our ancestors. Bipedalism caused great changes in the social organization and in the development of the culture as well. When and how this ability to move around on both legs appeared is a topic that has intrigued researchers for a long time.

The primate foot functions as a grasping organ. As such, its bones, soft tissues, and joints evolved to maximize power and stability in a variety of grasping configurations. However, humans are the obvious exception to this primate pattern, with feet that evolved to support the unique biomechanical demands of bipedal locomotion. We have lost, to a large extent, the prehensile ability of toes that the rest of the members of the group show.

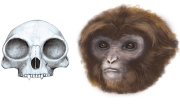

Now, an international team of researchers including Peter Fernandez (Stony Brook University, USA) and Sergio Almécija (also associated researcher at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusfont) have analyzed how the anatomy of the toes changed along time to facilitate bipedalism in the human lineage. Researchers have compared the structure of the joints between the metatarsus and the phalanges (at the base of the toes) of several species, ranging from fossil hominins to modern humans, including great apes (orangutans, gorillas and chimpanzees) and different species of monkeys.

The study reveals that the structure of Ardipithecus ramidus toes (the oldest bipedal hominin analyzed) already show certain adaptations to facilitate bipedalism. These changes rely in that joints between the metatarsus and the phalanges of the foot are oriented dorsally (upwards), which facilitates the extension of the joint and enhances the push-off power during bipedal locomotion. In contrast, other primates have oriented distally (downward) joints that allow flexion as feet are used mainly to grasp.

These changes emerged more than 4 million years ago and have been preserved in modern humans. However, the study also reveals that the big toe must have evolved quite late in comparison with the rest of the bones, suggesting that, until the appearance of first humans (over 2.2 million years ago) our ancestors still retained, to some extent, a relative prehensile ability with the big toe.

Why bipedalism emerged is a recurrent topic among the scientific community. A climate change that began in Africa around 7 million years ago caused a decrease in arboreal surface and the emergence of the current savannahs. This new landscape would have favoured the development of this locomotion system. At the same time, releasing hands from its locomotive function would have allowed the use upper extremities to other functions, such as the manufacture of tools.

Original article: Fernández, P.J, Mongle, C.S., Leakey, L., Proctor, D.J., Orr, C.M., Patel, B.A., Almécija, S., Tocheri, M.W., Jungers, W.L. (2018, published online). Evolution and function of the hominin forefoot. PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800818115

Related news: