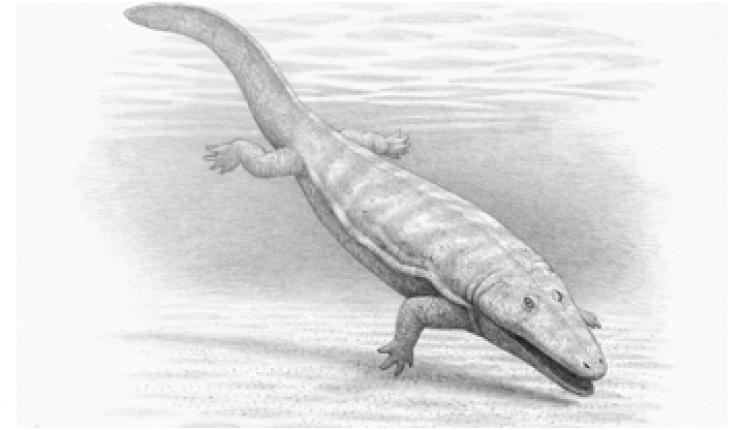

Reconstruction of the capitosaur Calmasuchus acri. Mauricio Anton. ICP

Capitosaurs were active predators with masticatory capabilities similar to those of some crocodiles. These are the results of the research recently published in the journal The Anatomical Record, signed by researchers of the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP) in collaboration with researchers from the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC). Capitosaurs were the largest amphibians that ever lived and became extinct about 215 million years.

From the study of 17 capitosaur taxa, the ICP researcher Josep Fortuny and his colleagues go deep into the morphological changes of the different species’ skulls and how they changed the way these animals fed. The results, published in the article "Skull Mechanics and the Evolutionary Patterns of the otic notch in Capitosaurs Closure (Amphibia: Temnospondyli)" show that these large carnivorous amphibians had an important diversity in the strength and breadth of the bite. The work has been recently published in the online edition of the journal of the American Association of Anatomy The Anatomical Record. Capitosaurs are known in every continent and taxa from around the world is analized in this wark, all of them older than 200 million years.

The catalan researchers have studied the evolution of different morphological features in the capitosaurs’ skulls and have obtained the stress distribution in the bone structure for different types of bite. The results are conclusive regarding their way of eating. While some extant amphibians, like most aquatic salamanders, make a powerful suction to capture their food, adult capitosaurs bite their prey without any suction, as do the crocodiles.

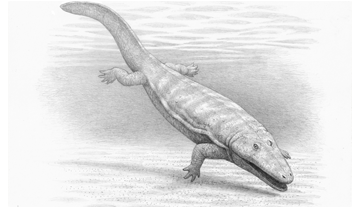

In the images of these two capitosaur skulls, Parotosuchus left and Eocyclotosaurus right, tabular horns (A) and the Otic Notch (B) are observed. ICP/UPC

"Apart from explaining how the capitosaurs fed, we also wanted to validate the hypothesis by paleontologist A. Howie from the 1970s , and here the results were somewhat surprising," says ICP researcher Josep Fortuny. Primitive capitosaurs of had posteriorly directed tabular horns, this are the bones where the muscles responsible for opening and closing the mouth are inserted. In more derived forms, however, they moved laterally to create a small island in the back of the skull, known as the otic notch. Howie argued that this evolution facilitated a more optimal bite, at the biomechanical level.

Contrary to this hypothesis, the results of the article show that the most primitive tabular horns were also optimal for the opening of the mouth. Thus, the evolutionary mechanisms that led to the closure of the otic notch do not have much to do with improved biomechanics of this movement, and more studies are needed to better understand these changes.

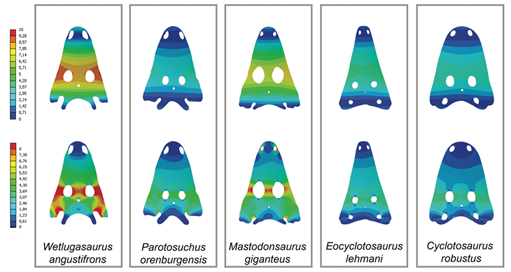

The calculation of the stress distribution in the capitosaurs’ skulls was performed using computational biomechanics methodologies, such as Finite Element Analysis (FEA) and Computer Aided Engineering (CAE). These techniques have allowed the creation of skull models to compare their structural response against the application of forces and the boundary conditions corresponding to different types of bite.

Capitosaurs are included in the big family of Temnospondyls, considered the predecessor of today's amphibians (such as frogs, salamanders and caecilians). Most extant amphibians are small, while capitosaurs easily exceeded a meter long and could reach six meters. Capitosaurs became extinct about 215 million years ago and, for decades, have been classified taking into account the morphology of the tabular horn.

In the images deformations (top) and stresses (bottom) are observed from simulations of a bilateral bite for several capitosaur species. ICP/UPC

Bites of wide range

In its most basal form, as is the case of Wetlugasaurus, skulls are weaker. As forms radiate, capitosaurs can generate a more powerful bite.

The elongation of the tabular horns, with the consequent closure of the otic notch, was taken for years as an indicator of a more powerful bite. This study shows, however, that Paratosuchus had one of the most powerful bites of the study group, along with Cyclotosaurus, although the otic notch is open and the tabular horns are not particularly long.

The ICP and UPC researchers have identified other morphological features such as the width of the skull and the snout length, which are equally or even more important than the tabular horns or the otic notch closure to understand capitosaurs bites.

This work, published by The Anatomical Record follows a study published last summer, which showed how the earliest forms of tetrapods, among which capitosaurs are included, diversified to occupy niches in both aquatic and terrestrial environments.